Editor's Note: Frances Shure, M.A., L.P.C., has performed an in-depth analysis addressing a key issue of our time: "Why Do Good People Become Silent — or Worse — About 9/11?" The resulting essay, being presented here as a series, is a synthesis of both academic research and clinical observations.

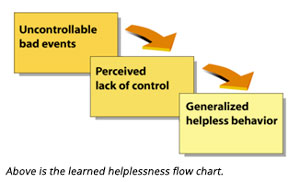

In this installment, we continue Ms. Shure's analysis with "Part 14: Learned Helplessness," a conditioned response to trauma or adversity that involves ongoing pain as well as actual or perceived lack of control.

Please note that because Architects & Engineers for 9/11 Truth is dedicated to researching and disseminating scientific information about the destruction of three World Trade Center skyscrapers on September 11, 2001, and does not speculate as to the identity or motives of the perpetrators, any reference to names or motives of the attackers in this series of articles, made by either the author or the individuals she quotes, is a personal opinion and not the viewpoint of AE911Truth.

“I can see that 9/11 was a false flag operation, but there is nothing I can do to make a difference,” a male friend quietly admitted to me.

He is one of several friends who, in the years since September 11, 2001, have made similar remarks when I have asked them to tell me their thoughts about the evidence that refutes the official account of 9/11.

A female friend made another such statement, forcefully declaring, “If this is true about 9/11, then we’re in much worse shape than any of us have thought. This is way, way bigger than I am. In this case, perhaps evil will just need to run its course. There is nothing I can do.”

Then there was the man I met at the Denver People’s Fair, who hurried away from me to avoid any further conversation, simultaneously explaining, to my astonishment: “I agree with you that 9/11 was a false-flag operation. But this is what those in power have done to the rest of us for centuries. It will continue into the future, and there is nothing we can ever do to stop it.”

Still another acquaintance, upon hearing for the first time some of the unanswered questions surrounding 9/11, blurted out one of my favorite retorts: “What! I’ve never heard of this! Listen! If you are going to go after Sauron, you’d better be sure you have the ring!”His colorful declaration meant that without supernatural power, such an ambitious undertaking would be hopeless.1

I have long wondered if people with responses like these could be victims of “learned helplessness,” a psychological condition that was discovered by Martin E. P. Seligman and colleagues when they performed a series of brutal experiments that began with dogs as the subjects.

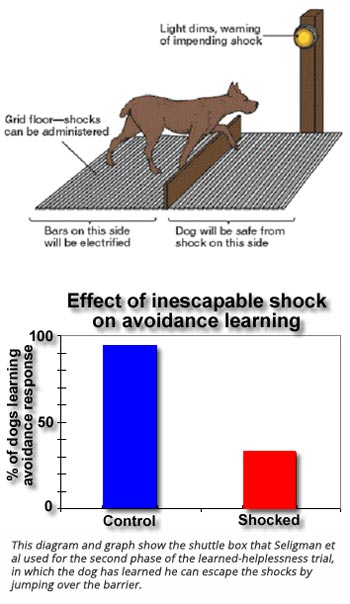

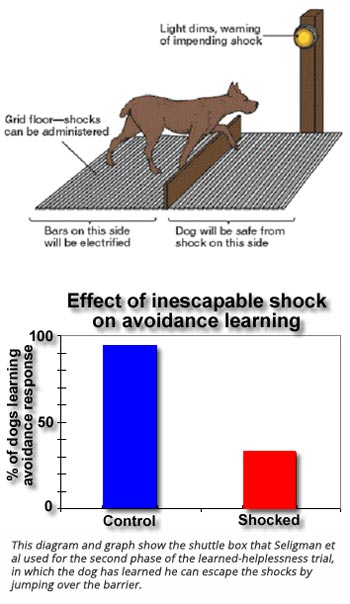

In the 1960s, Seligman et al subjected approximately 150 harnessed and restrained dogs to a series of 64 moderately painful and inescapable electric shocks on the first day of each trial. It didn't take the dogs long during that first phase to “learn” that they could not escape the torture. Soon they gave up trying and passively submitted to the pain, whining and sometimes rolling over in a submissive posture.

The second phase of the trial began 24 hours later. In it, the canine subjects were each put in a shuttle box, a two-sided chamber with a barrier in the middle that the dog could jump over — an action that would automatically turn off the shocks, allowing the dog to escape the pain. Additionally, a dimming light was used to signal that the next shock would come in 10 seconds, so that the dog could not only learn to escape the shocks, but could also eventually learn to avoid the shocks altogether by jumping the barrier as soon as he saw the light dim.

“Naïve” dogs, who2 had not undergone the first phase of the trial with the inescapable shocks, quickly learned to escape the shocks in the shuttle box by jumping the barrier. They also eventually learned to avoid the shocks altogether by jumping when they saw the light begin to dim.

The very first time they were shocked in the shuttle box, the dogs in both groups ran around frantically for about thirty seconds. But after that, two-thirds of the first group of canines — those who had been given the first inescapable trial — showed a strikingly different pattern from the naïve dogs. Instead of discovering they could jump to safety, these dogs gave up, lying down and quietly whining while the shocks continued for 60 more seconds, at which time the trial ended.

To the surprise of the researchers, the same two-thirds of these traumatized dogs failed to escape in all of the succeeding trials. They had “learned” to feel helpless and hopeless. In other words, they had generalized their initial inescapable trauma, feeling trapped in all future escapable traumatic situations.

Interestingly, the other one-third of the traumatized dogs did learn to escape the shocks in the shuttle box as effectively as the naïve dogs.

Of the approximately 100 dogs that had been conditioned to learned helplessness, Seligman summarizes:

Laboratory evidence shows that when an organism has experienced trauma it cannot control, its motivation to respond in the face of later trauma wanes. Moreover, even if it does respond, and the response succeeds in producing relief, it has trouble learning, perceiving, and believing that the response worked. Finally, its emotional balance is disturbed: depression and anxiety, measured in various ways, predominate.3

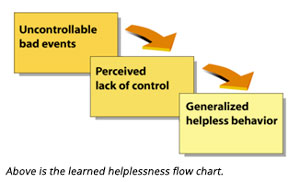

The key to learned helplessness, then, is actual or perceived lack of control.4

Variations of this study, conducted by Seligman and by other researchers, have demonstrated that whether the subjects are dogs, cats, rats, fish, monkeys, or humans, being subjected to uncontrollable trauma produces a marked decrease in one’s ability to respond adaptively to future controllable trauma.

Moreover, researchers have found that learned helplessness does not have to be the result of trauma. All that is needed to affect future behavior is an inescapable adverse event, such as an uncontrollable loud noise. Uncontrollable adverse events, they have discovered, tend to decrease the subject’s motivation to escape from frustration, retard his ability to solve problems or to learn in general, and chill his normal aggressive or defensive responses to future adverse events.

Seligman and his colleagues determined that people with the learned-helplessness condition express themselves with pessimism when they explain challenging situations. Expressions such as “It will never change” . . . “It’s my fault” . . . “I’m stupid” . . . “It’s going to last forever” . . . “All teachers are unfair” . . . “Diets never work” are clues that the speaker likely suffers from learned helplessness. These words convey the learned beliefs of: 1) permanence – the bad events or circumstances he faces are permanent, not temporary; 2) pervasiveness – a failure in one area of his life will automatically pervade all aspects of his life; and 3) low self-esteem – a sense of being inherently worthless, unlovable, and talentless.5

Learned helplessness, the researchers also discovered, is associated with subsequent depression, anxiety, phobias, shyness, and/or loneliness.6

The good news, however, is that learned helplessness is reversible. Seligman et al determined, after much trial and error, that the dogs who were conditioned to feel helpless could in fact be rehabilitated through “directive therapy.” The researchers removed the barrier in the shuttle box and, after the shocks began, used a leash to drag the dogs to the other side of the box, thus forcibly removing them from the electricity. After being pulled anywhere between 25 and 200 times, all the dogs finally responded on their own. Then, when the researchers replaced the barrier and gradually built it higher, these formerly helpless dogs continued to escape the electric shocks by jumping the barrier. Their recovery from helplessness proved to be complete and lasting.

Let’s now recall that one-third of the dogs who were subjected to the inescapable shocks acted just like the naïve dogs in the shuttle box. Why were these dogs apparently immune to being conditioned to learned helplessness? The answer most likely lies in subsequent studies, which have demonstrated that animals and people who have a history of experiences with controllable trauma — in other words, trauma that they managed to master with their own efforts (and this criterion is key) — became immune to learned helplessness. Therefore, even when these beings are subjected to a traumatic situation later on, in which the outcome is actually uncontrollable, they remain unconvinced that they are now powerless. “This,” says Seligman, “is the heart of the concept of immunization.”7

Of course, the opposite is also true: A past history of experiences in which there was no escape will make it difficult for the human or animal to believe that an outcome is controllable, even when it actually is.

These discoveries have profound implications for child rearing. Infants, children, and adolescents who are subjected to uncontrollable trauma or adverse events have a poor self-image. They become hopeless, unmotivated, depressed or anxious, and they fail to learn. These children become the very adults who, when subjected to the evidence that refutes the official 9/11 storyline, might run in the other direction to avoid the messenger — or, if cornered or pressed, quietly admit, “There is nothing I can do to make a difference” (or a variation thereof).

In my psychotherapeutic work, I discovered that some of my clients had experienced severe traumas during their birth process, their preverbal years, or their childhoods. These early, overwhelming traumas caused these individuals to respond automatically with a feeling of powerlessness whenever they were faced with a challenging situation. One example that comes to mind is the person who, as an infant, was reared in dire poverty. Her overworked, exhausted mother was largely unavailable, both physically and emotionally during her infancy and childhood. None of her attempts to get her mother to care for her succeeded, making this an uncontrollable situation. Another example I recall is the toddler who was left alone in a hospital for weeks on end without his mother or father present to comfort him. Both individuals, not surprisingly, suffered from subsequent depression and low self-esteem.

Another illustration of learned helplessness comes from the work of psychiatrist Stanislav Grof, who has documented many examples of birth trauma. If, for example, the second stage of birth is prolonged, with intense uterine contractions and a cervix not fully opened, the child is subjected to an uncontrollable, inescapable, and seemingly interminable battering from the contractions. No effort on the child's part can change this “no exit” situation. Babies who have undergone this birth trauma, Grof discovered, can develop “inhibited depression” later in life, even if other events in their subsequent development were benign. Inhibited depression is characterized by feelings of inferiority, inadequacy, helplessness, hopelessness, and existential despair. In other words, the uncontrollable aspect of trauma at this stage of birth can result in learned helplessness.8

Learned-helplessness conditioning can be established in adulthood as well. Victims of torture and troops who served in a war are liable to suffer from a condition that has been labeled Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). As with the childhood and animal-research cases, if these adults exhibit signs of learned helplessness, it is an indication that they were probably subjected to a prolonged traumatic event that was uncontrollable.

If those who unconsciously harbor uncontrollable traumatic histories hear that they have been brutally lied to and that their fellow Americans have been mass-murdered by their own government, the old, unconscious emotional reactions of being overwhelmed and helpless in infancy and childhood are likely reactivated, causing great distress and fear. These emotions are immediately followed by defensive responses such as avoidance, resignation, and/or apathy. Though the source of learned helplessness in humans often lies deep within the unconscious psyche, the condition can be healed through extensive psychotherapeutic work. Before healing is accomplished, however, any attempt to logically explain the 9/11 Truth evidence to such a traumatized person will probably fall on infertile ground.

Clearly, 9/11 is not the only tragic event in recent history that elicits a reaction of learned helplessness. The toxic cocktail of corruption, violence, and dysfunction so prevalent in today’s world can easily activate old traumas, reigniting feelings of being overwhelmed and hopeless. But then again, anyone with a modicum of awareness and sensitivity to the plight of other beings and the earth itself is rightly disturbed by the realities of today’s world.9

As activists, we need to heal our own anxiety and overarching sense of urgency to cultivate the understanding and compassion that allow us to empathize with people burdened by such internal handicaps as learned helplessness. These individuals are probably coping as best they can. Unless their wounds are healed, all the mountains of evidence we share with them about 9/11 Truth will likely make them feel disempowered and will thus be summarily rejected.

While the phenomenon of learned helplessness is backed by copious research, a concept called “the abuse syndrome” has not yet received this backing. Nonetheless, the abuse syndrome deserves to be considered as a possible explanation for reactions of helplessness, hopelessness, and apathy. We will explore it in the next segment of this series.

Endnotes

1 Sauron is the main antagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The cursed ring, which was to be destroyed by the relatively pure hero Frodo Baggins, seduced even the most pure of beings who possessed it into an insatiable lust for power. My acquaintance was implicating that if we were going to challenge such evil as was perpetrated on 9/11, then we had better have a ring of evil power in our possession.

2 After a conversation with one of my editors, I agreed with her that we should help raise consciousness about the plight of animals in our world. We have been trained in our culture to think of non-human beings as objects, even commodities — and as much less important than humans. The everyday language we use is one way to increase our awareness that animals feel, both physically and emotionally. They respond to pain, imprisonment, or betrayal with fear and anguish and confusion. They also respond to being treated with compassion, respect, and love. Thus, in this essay, I will use the pronoun “who” rather than “that” in referring to these innocents. To those who want to witness the profound sensitivity and intelligence of animals, I highly recommend one of the most beautiful films I have seen: The Animal Communicator, which may be watched or purchased online.

3 Martin E. P. Seligman, Helplessness: On Depression, Development, and Death (W.H. Freeman & Co., May 1992), 22 – 23.

4 Seligman, Helplessness.

5 Ibid. xx – xxiv.

6 Seligman, Helplessness

7 Ibid.60.

8 Stanislav Grof, Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death and Transcendence in Psychotherapy (State University of New York, 1985).

Stanislav Grof, The Adventure of Self-Discovery: Dimensions of Consciousness and New Perspectives in Psychotherapy and Inner Exploration (State University of New York Press, 1988).

Stanislav Grof is a world-renowned pioneer of psychodynamic and transpersonal psychology.

9 Dennis, Sheila, and Mathew Linn, Healing the Future. The Linns tell their personal stories of healing from societal trauma, activated by earlier developmental trauma, offering examples of simple healing exercises.

Note: Electronic sources in the endnotes have been archived. If they can no longer be found by a search on the Internet, readers desiring a copy may contact Frances Shure for a copy [ This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. ].

In the 1960s, Seligman et al subjected approximately 150 harnessed and restrained dogs to a series of 64 moderately painful and inescapable electric shocks on the first day of each trial. It didn't take the dogs long during that first phase to “learn” that they could not escape the torture. Soon they gave up trying and passively submitted to the pain, whining and sometimes rolling over in a submissive posture.

In the 1960s, Seligman et al subjected approximately 150 harnessed and restrained dogs to a series of 64 moderately painful and inescapable electric shocks on the first day of each trial. It didn't take the dogs long during that first phase to “learn” that they could not escape the torture. Soon they gave up trying and passively submitted to the pain, whining and sometimes rolling over in a submissive posture. These discoveries have profound implications for child rearing. Infants, children, and adolescents who are subjected to uncontrollable trauma or adverse events have a poor self-image. They become hopeless, unmotivated, depressed or anxious, and they fail to learn. These children become the very adults who, when subjected to the evidence that refutes the official 9/11 storyline, might run in the other direction to avoid the messenger — or, if cornered or pressed, quietly admit, “There is nothing I can do to make a difference” (or a variation thereof).

These discoveries have profound implications for child rearing. Infants, children, and adolescents who are subjected to uncontrollable trauma or adverse events have a poor self-image. They become hopeless, unmotivated, depressed or anxious, and they fail to learn. These children become the very adults who, when subjected to the evidence that refutes the official 9/11 storyline, might run in the other direction to avoid the messenger — or, if cornered or pressed, quietly admit, “There is nothing I can do to make a difference” (or a variation thereof).